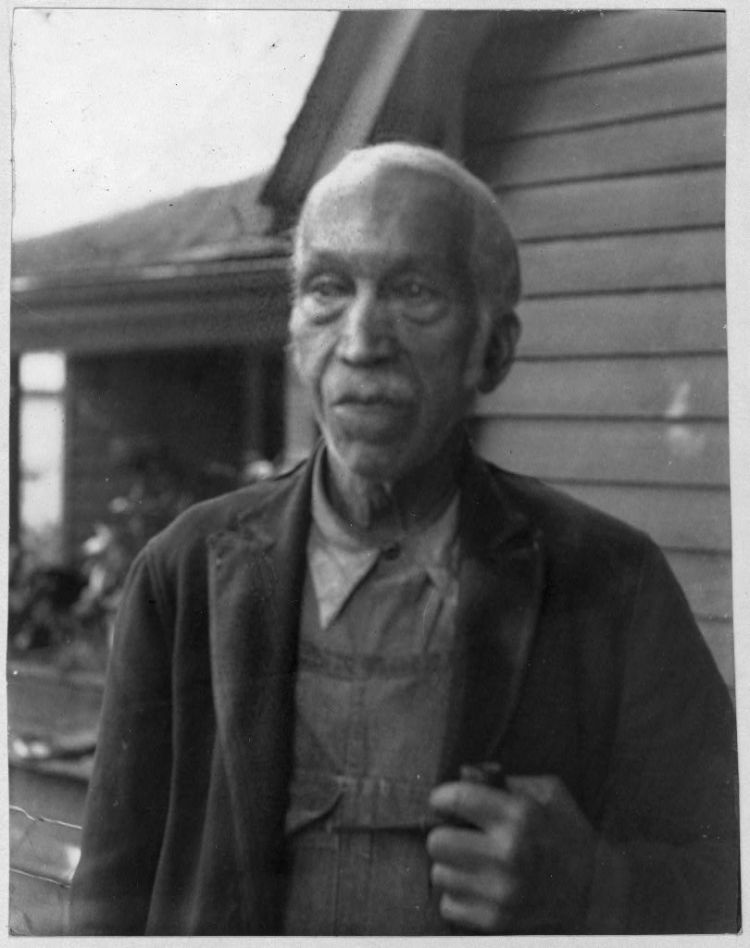

Photograph of Martin Luther Bost, age 88, taken between 1936 and 1938 for the WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project (Library of Congress).

Enslaved in Catawba County

Biography

Believed to have been born in December of 1851, Martin Luther (M. L.) Bost and his family were enslaved by Jonas Bost in Newton, North Carolina until their emancipation, after which they worked locally for Solomon Hall. Eventually, M. L. moved to Asheville and purchased a piece of property in the 1890s where he built a home and raised two daughters and an adopted son with his wife, Mary Eliza Donald Bost. On September 27, 1937, “W. L. Bost” [sic] was interviewed about his experience during his enslavement as part of the Federal Writers’ Project in the Works Progress Administration (WPA). His photograph and narrative, as told by Marjorie Jones (believed to have been a locally notable social worker in Western North Carolina during the 1950-70s), are part of the “Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–1938” collection at the National Archives. M. L. Bost died at his home in Asheville on April 4, 1939 and was interred at the Violet Hill Cemetery, one of Asheville’s oldest African-American cemeteries.

Context

Available primary on microfilm until they were finally digitized in 2000-2001, these WPA interviews remain a crucial, if compromised, source of evidence and a important corrective to mainstream Lost Cause narratives of the time that offered gentile criticisms of slavery and strong condemnation of “Negro rule” during Reconstruction. As Catherine A. Stewart explains in Long Past Slavery from The University of North Carolina Press (2016), the “compromising circumstances of the color line in 1930s America made it almost impossible for blacks and whites to speak to one another freely about slavery.”

In this context the Bost narrative and the narrative of Sarah Gudger of Old Fort, also captured by Marjorie Jones – a young white woman believed to be a local social worker – are notable. Compare these narratives to the one of Josephine Anderson captured by Jules Frost, a white man and former journalist who titled his narrative “Mama Duck” and concluded with an excerpt from a “good” slaveholder on the harmony that existed between slave and master):

“Anderson’s haunting takes place, not incidentally, on the railroad tracks—often a southern town’s dividing line between white and black communities and a powerful metaphor for highly charged racial geographies resulting from Jim Crow…

Catherine Stewart (2016)

Her ghost story provides a coded and oblique commentary on the boundaries of the color line, both visible and invisible, but always a felt and marked presence, much like the ghost in Anderson’s tale. The railroad ties represent a liminal site or threshold where interracial contact may take place, but such close proximity raises questions about transgression and the unequal risk such contact posed for African Americans; the possibility that his whiteness is corporeal may be even more frightening than if it is ethereal.”

For a “much broader story of how African Americans experienced the transition from slavery to freedom,” Carole Emberton’s new book, To Walk About in Freedom: The Long Emancipation of Priscilla Joyner, “does a masterful job of reconstructing” the life of a woman who lived in Nash County, near Rocky Mount, North Carolina, based on her WPA narrative and sparse additional primary sources, by “exploring the experiences of other individuals, who faced similar challenges” and “acknowledging what the evidence allows her to conclude and where speculation must suffice” (Kevin M. Levin).

Bost’s narrative (PDF) was published in My Folks Don’t Want Me To Talk About Slavery, with his photograph on the cover of the book, by Belinda Hurmence of Winston-Salem in 1984. A paperback copy of Hurmence’s book is now available in the Rhodes Room at the Newton branch library (donated by Catawba County Truth & Reconciliation Committee), and the book should now be in general circulation at the Catawba County Library. Available broadly on the internet today in text form, audio of a LibriVox reading is also available now in the public domain. Portions of Bost’s narrative were read by Ossie Davis for the HBO documentary Unchained Memories (2003). Bost’s complete narrative is included in The North Carolina Slave Narratives Vol, 1 A-H, published by Stephen Payseur (2013), and the Catawba Valley Interfaith Council hosted a local reading by Rev. Reggie Longcrier in 2023 (which is available on Facebook) However, neither Bost’s name nor his narrative appear in either of our official county histories (published in 1954 and 1995), nor are there any historical markers or monuments commemorating Bost. On the other hand, the man who enslaved him is discussed extensively in both of our official county histories. Jonas “served as chairman of the county court and handled the purchase of land for the new county seat of Newton.” He built the original Catawba County courthouse and “the first stocks, pillory, and whipping post near the courthouse” (Bishir, 2009). Jonas also operated a prominent hotel in Newton, which is where the Catawba Superior Court stayed during their first visit to Newton in 1849. The Bost House was located across the southwest corner from the courthouse, where the “speculators” stayed and enslaved people were bought and sold at auctions as discussed in M. L. Bost’s narrative below. In 1907, the Catawba County Confederate soldiers monument was erected on the grounds of original courthouse that Jonas built (which was replaced in 1924 and now serves as the Catawba County Museum of History).

“[W]hat was most striking about the room [inside the National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C. in which these narratives are featured] was the voices running through it. The words of people who had survived slavery were running on a six-minute loop. Their voices floated through the air like ghosts…When I first came across the narratives, I was confused as to why I had never, not once in my entire education, been made aware of their existence. It was as if this trove of testimony—accounts that might expand, complicate, and deepen my understanding of slavery—had purposefully been kept from view.”

– Clint Smith (from The Atlantic, March 2021), author of ‘How the Word is Passed’ (2021)

Narrative

IMPORTANT: This interview was conducted during the Jim Crow era and contains dehumanizing language and disturbing graphic personal recollections about the American Civil War antebellum period and Reconstruction era. Told by a young white woman (believed to have later been a locally notable social worker in Western N.C.), this narrative text is “derived from oral interviews” and “usually involve some attempt by the interviewers to reproduce in writing the spoken language of the people they interviewed,” as explained by the Library of Congress, “in accordance with instructions from the project’s headquarters, the national office of the Federal Writers’ Project in Washington, D.C.” in the late 1930s. However, we are reproducing it here as it originally appeared, without euphemistic substitutions, in order to honestly reflect the troubling themes of identity and human behavior at the heart of this disturbing history.

My Massa’s name was Jonas Bost. He had a hotel in Newton, North Carolina. My mother and grandmother both belonged to the Bost family. My ole Massa had two large plantations one about three miles from Newton and another four miles away. It took a lot of niggers to keep the work a goin’ on them both. The women folks had to work in the hotel and in the big house in town. Ole Missus she was a good woman. She never allowed the Massa to buy or sell any slaves. There never was an overseer on the whole plantation. The oldest colored man always looked after the niggers. We niggers lived better than the niggers on the other plantations.

Lord child, I remember when I was a little boy, ’bout ten years, the speculators come through Newton with droves of slaves. They always stay at our place. The poor critters nearly froze to death. They always come ’long on the last of December so that the niggers would be ready for sale on the first day of January. Many the time I see four or five of them chained together. They never had enough clothes on to keep a cat warm. The women never wore anything but a thin dress and a petticoat and one underwear. I’ve seen the ice balls hangin’ on to the bottom of their dresses as they ran along, jes like sheep in a pasture ’fore they are sheared. They never wore any shoes. Jes run along on the ground, all spewed up with ice.

The speculators always rode on horses and drove the pore niggers. When they get cold, they make ’em run ’til they are warm again. The speculators stayed in the hotel and put the niggers in the quarters jes like droves of hogs. All through the night I could hear them mournin’ and prayin’. I didn’t know the Lord would let people live who were so cruel. The gates were always locked and they was a guard on the outside to shoot anyone who tried to run away. Lord miss, them slaves look jes like droves of turkeys runnin’ along in front of them horses.

I remember when they put ’em on the block to sell ’em. The ones ’tween 18 and 30 always bring the most money. The auctioneer he stand off at a distance and cry ’em off as they stand on the block. I can hear his voice as long as I live.

If the one they going to sell was a young Negro man this is what he say: “Now gentlemen and fellow citizens here is a big black buck Negro. He’s stout as a mule. Good for any kin’ o’work an’ he never gives any trouble. How much am I offered for him?” And then the sale would commence, and the nigger would be sold to the highest bidder.

If they put up a young nigger woman the auctioneer cry out: “Here’s a young nigger wench, how much am I offered for her?” The pore thing stand on the block a shiverin’ an’ a shakin’ nearly froze to death. When they sold many of the pore mothers beg the speculators to sell ’em with their husbands, but the speculator only take what he want. So maybe the pore thing never see her husban’ agin.

Ole’ Massa always see that we get plenty to eat. O’ course it was no fancy rashions. Jes corn bread, milk, fat meat, and ’lasses but the Lord knows that was lots more than other pore niggers got. Some of then had such bad masters.

Us pore niggers never ’lowed to learn anything. All the readin’ they ever hear was when they was carried through the big Bible. The Massa say that keep the slaves in they places. They was one nigger boy in Newton who was terrible smart. He learn to read an’ write. He take other colored children out in the fields and teach ’em about the Bible, but they forgit it ’fore the nex’ Sunday.

Then the paddyrollers they keep close watch on the pore niggers so they have no chance to do anything or go anywhere. They jes’ like policemen, only worser. ’Cause they never let the niggers go anywhere without a pass from his master. If you wasn’t in your proper place when the paddyrollers come they lash you til’ you was black and blue. The women got 15 lashes and the men 30. That is for jes bein’ out without a pass. If the nigger done anything worse he was taken to the jail and put in the whippin’ post. They was two holes cut for the arms stretch up in the air and a block to put your feet in, then they whip you with cowhide whip. An’ the clothes shore never get any of them licks.

I remember how they kill one nigger whippin’ him with the bull whip. Many the pore nigger nearly killed with the bull whip. But this one die. He was a stubborn Negro and didn’t do as much work as his Massa though he ought to. He been lashed lot before. So they take him to the whippin’ post, and then they strip his clothes off and then the man stan’ off and cut him with the whip. His back was cut all to pieces. The cuts about half inch apart. Then after they whip him they tie him down and put salt on him. Then after he lie in the sun awhile they whip him agin. But when they finish with him he was dead.

Plenty of the colored women have children by the white men. She know better than to not do what he say. Didn’t have much of that until the men from South Carolina come up here and settle and bring slaves. Then they take them very same children what have they own blood and make slaves out of them. If the Missus find out she raise revolution. But she hardly find out. The white men not going to tell and the nigger women were always afraid to. So they jes go on hopin’ that thing won’t be that way always.

I remember how the driver, he was the man who did most of the whippin’, use to whip some of the niggers. He would tie their hands together and then put their hands down over their knees, then take a stick and stick it ’tween they hands and knees. Then when he take hold of them and beat ’em first on one side then on the other.

Us niggers never have chance to go to Sunday School and church. The white folks feared for niggers to get any religion and education, but I reckon somethin’ inside jes told us about God and that there was a better place hereafter. We would sneak off and have prayer meetin’. Sometimes the paddyrollers catch us and beat us good but that didn’t keep us from tryin’. I remember one old song we use to sing when we meet down in the woods back of the barn. My mother she sing an’ pray to the Lord to deliver us out o’ slavery. She always say she thankful she was never sold from her children, and that our Massa not so mean as some of the others. But the old song it went something like this:

“Oh, mother lets go down, lets go down, lets go down, lets go down.

Oh, mother lets go down, down in the valley to pray.

Studyin’ about that good ole way

Who shall wear that starry crown.

Good Lord show me the way.”Then the other part was just like that except it said “father” instead of “mother,” and then “sister” and then “brother.”

Then they sing sometime:

“We camp a while in the wilderness, in the wilderness, in the wilderness.

We camp a while in the wilderness, where the Lord makes me happy

And then I’m a goin’ home.”I don’t remember much about the war. There was no fightin’ done in Newton. Jes a skirmish or two. Most of the people get everything jes ready to run when the Yankee sojers come through the town. This was toward the las’ of the war. Cose the niggers knew what all the fightin’ was about, but they didn’t dare say anything. The man who owned the slaves was too mad as it was, and if the niggers say anything they get shot right then and thar. The sojers tell us after the war that we get food, clothes, and wages from our Massas else we leave. But they was very few that ever got anything. Our ole Massa say he not gwine pay us anything, corse his money was no good, but he wouldn’t pay us if it had been.

Then the Ku Klux Klan come ’long. They were terrible dangerous. They wear long gowns, touch the ground. They ride horses through the town at night and if they find a Negro that tries to get nervy or have a little bit for himself, they lash him nearly to death and gag him and leave him to do the bes’ he can. Some time they put sticks in the top of the tall thing they wear and then put an extra head up there with scary eyes and great big mouth, then they stick it clear up in the air to scare the poor Negroes to death. They had another thing they call the “Donkey Devil” that was jes as bad. They take the skin of a donkey and get inside of it and run after the pore Negroes. Oh, Miss[,] them was bad times, them was bad times. I know folks think the books tell the truth, but they shore don’t. Us pore niggers had to take it all.

Then after the war was over we was afraid to move. Jes like tarpins or turtles after ’mancipation. Jes stick our heads out to see how the land lay. My mammy stay with Marse Jonah for ’bout a year after freedom then ole Solomon Hall made her an offer. Ole man Hall was a good man if there ever was one. He freed all of his slaves about two years ’fore ’mancipation and gave each of them so much money when he died, that is he put that in his will. But when he die his sons and daughters never give anything to the pore Negroes. My mother went to live on the place belongin’ to the nephew of Solomon Hall. All of her six children went with her. Mother she cook for the white folks an’ the children make crop. When the first year was up us children got the first money we had in our lives. My mother certainly was happy.

We live on this place for over four years. When I was ’bout twenty year old I married a girl from West Virginia but she didn’t live but jes ’bout a year. I stayed down there for a year or so and then I met Mamie. We came here and both of us went to work, we work at the same place. We bought this little piece of ground ’bout forty-two years ago. We gave $125. for it. We had to buy the lumber to build the house a little at a time but finally we got the house done. Its been a good home for us and the children. We have two daughters and one adopted son. Both of the girls are good cooks. One of them lives in New Jersey and cooks in a big hotel. She and her husband come to see us about once a year. The other one is in Philadelphia. They both have plenty. But the adopted boy, he was part white. We took him when he was a small and did the best we could by him. He never did like to ’sociate with colored people. I remember one time when he was a small child I took him to town and the conductor made me put him in the front of the street car cause he thought I was just caring for him and he was a white boy. Well, we sent him to school until he finished. Then he joined the navy. I ain’t see[n] him in several years. The last letter I got from him he say he ain’t spoke to a colored girl since he has been there. This made me mad so I took his insurance policy and cashed it. I didn’t want nothin’ to do with him, if he deny his own color.

Very few of the Negroes ever get anywhere; they never have no education. I knew one Negro who got to be a policeman in Salisbury once and he was a good one too. When my next birthday comes in December I will be eighty-eight years old. That is if the Lord lets me live and I shore hope He does.

Source: WPA Slave Narrative Project (North Carolina Narratives, Vol. 2, Part 1), Federal Writers’ Project, U.S. Work Projects Administration (USWPA).

“My sister and I visited him at his house when I was [a] little girl. He was always very nice to me. He always gave me and my sister candy and a few pennies. He raised pigeons and liked to take us out back and show them to us.”

– Cora Hopper, M. L. Bost’s great-granddaughter

Interviewed by Rob Neufeld (Asheville Citizen-Times, 2014)